Extending Kubernetes with Metacontroller

Kubernetes is great for many reasons. It is very good for orchestrating workload over multiple nodes in a cluster. But I think that the extensibility of it is what makes Kubernetes so powerful. This gives us endless possibilities.

Kubernetes controllers

As said in the intro, Kubernetes is a platform for orchestrating containerized workloads across a cluster.

One of the key components of the cluster is the control plane.

The control plane contains components which ensures that Kubernetes actualizes the “desired state”.

The desired state is the thing that the user defines in YAML or JSON format.

One example is that the user can define a Deployment of two replicas. As a result, the control plane ensures that ultimately two Pods are spun up.

Kubernetes achieves this by employing the controller pattern.

A controller is responsible for making the current state of the cluster, the desired state.

It does so by tracking at least one Kubernetes resource type.

This can be a Deployment, Job or a custom type (defined by a Custom Resource Definition - CRD).

This article explains how to create custom controllers and resources. Several frameworks are built to facilitate this, for example kubebuilder, KUDO and Metacontroller. For this article we will use Metacontroller.

Metacontroller

Creating a controller using tools, such as kubebuilder, can be really difficult. It requires deep knowledges of both the Kubernetes inner workings and the Golang language. Metacontroller takes away that complexity, allowing people to create controllers in a relatively simple manner. By implementing Metacontroller CRDs, users define which resource type should be watched, also called the parent resource.

So, how does it work? Once such a resource changes, an HTTP webhook is executed against a configurable URL. The URL will typically be pointed to an HTTP endpoint, which is created and managed by the user. The endpoint’s implementation calculates the desired state based on the data in the request and returns that in the response. The request contains, among other data, the (watched) parent resource. Lastly, Metacontroller ensures that the desired state is applied to the cluster.

That is right, Metacontroller just calls an HTTP endpoint once a watched resource changes. There are no limitations to the technology that can be used for building the webservice containing the HTTP endpoint with. Also, there are no difficult low-level Kubernetes concepts to deal with.

Controller types

Metacontroller offers two different controller types:

- The composite controller allows developers to create and manage new child resources. Think of a

DeploymentmanagingReplicaSets, which itself managesPods. - The decorator controller allows for changing the watched parent resource itself. Think of a controller automatically adding sidecars to

Pods.

This article will show an example of the former one, the composite controller.

Put into practice - PythonLambda Operator

So, the composite controller can spawn and manage child resources. Let’s think of an example project which illustrates a use-case. Perhaps something that is easily configured on the surface, but requires quite some machinery to work…

Introducing… the PythonLambda operator!

Python refers to the programming language (surprisingly not the snake), and “Lambda” is a wink to the AWS Function-as-a-Service capability. With a Function-as-a-Service, developers only have to care about the code they want to run. The infrastructure takes care of hosting it and scaling it up and down depending on the load. This article explains how to utilize Metacontroller to create a simple Function-as-a-Service capability yourself (who needs a cloud vendor nowadays?). As promised, the developer will only have to define a single resource defining his code, and our operator will take care of the rest.

Operator?

You may be thinking, where is the term “operator” suddenly coming from? Well, it is not universely defined, but it’s often referred to as a Kubernetes-native application. The following quote is part of the definion from the Operator Framework:

With Operators you can stop treating an application as a collection of primitives like Pods, Deployments, Services or ConfigMaps, but instead as a single object that only exposes the knobs that make sense for the application.

source: https://operatorframework.io/

Overview

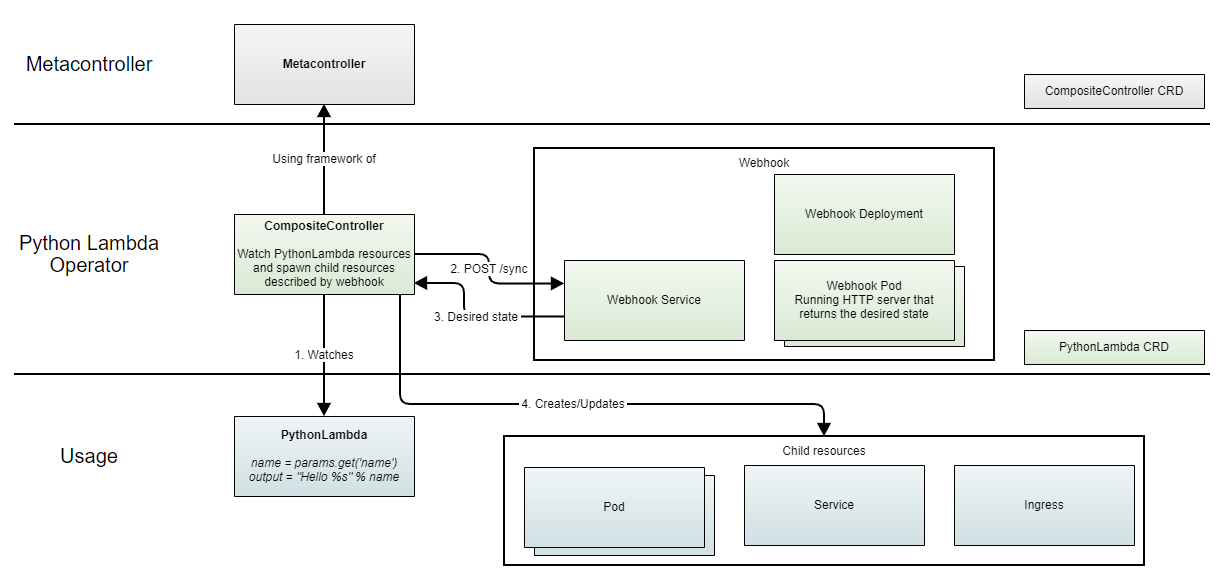

The overview is composed of three horizontal layers:

- The first layer is what is installed with Metacontroller.

- The second layer contains the PythonLambda operator components, which have to run before it can be used. This contains the implemented Composite Controller and the webhook service which calculates the desired state.

- The third layer is the usage layer, where zero to multiple PythonLambda resources can be deployed and where the child resources end up based on the calculated desired state.

The components are explained in more detail below:

CRD

As the quote says, an Operator has a single object as interface. After defining the interface as a CRD and deploying that to the cluster, the developer can deploy resources of that type.

But first, here is the definition of the CRD:

apiVersion: apiextensions.k8s.io/v1beta1

kind: CustomResourceDefinition

metadata:

name: pythonlambdas.example.com

spec:

group: example.com

version: v1

names:

kind: PythonLambda

plural: pythonlambdas

singular: pythonlambda

shortNames:

- py

scope: Namespaced

subresources:

status: {}This YAML can be applied to your Kubernetes cluster like any other resource definition. While this is all that is needed to add your own resource definition, usually these manifests contain a spec schema defined in the Open API standard. Kubernetes will not accept manifests which do not follow the scheme. Sometimes they also contain different versions of the schema, and even automatic version translations. We skip that to keep our example brief.

Controller

Once developers deploy resources of our PythonLambda type, we have to act.

This is where the CompositeController comes in:

apiVersion: metacontroller.k8s.io/v1alpha1

kind: CompositeController

metadata:

name: python-lambda-operator

namespace: python-lambda-operator

spec:

generateSelector: true

parentResource:

apiVersion: example.com/v1

resource: pythonlambdas

childResources:

- apiVersion: v1

resource: configmaps

updateStrategy:

method: Recreate

- apiVersion: v1

resource: services

updateStrategy:

method: Recreate

- apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1beta1

resource: ingresses

updateStrategy:

method: InPlace

- apiVersion: v1

resource: pods

updateStrategy:

method: Recreate

hooks:

sync:

webhook:

url: http://webhook-python-lambda-operator.python-lambda-operator/syncWe define a controller of the type CompositeController and tell it to watch a certain parent resource type: the pythonlambdas type.

We also define what kind of child resources can be created and managed under this parent resource.

The following child resources are created:

- ConfigMap: This is where the generated Python HTTP server script is stored, including the script of the developer.

- Pod: One or multiple

Podswill run the Python script from theConfigMap. - Ingress: This allows us to expose our HTTP server to the outside.

- Service: The service is created to connect our

Ingressto ourPods.

Finally, the endpoint for the sync webhook is specified.

This is the URL that will be called once a PythonLambda resource changes.

In this case, it will call the webhook-python-lambda-operator Service in the python-lambda-operator namespace, on the /sync endpoint.

Webhook service implementation

Now we have to create an HTTP service which calculates the child resources based on changes of the PythonLambda resource.

This service can be written in any programming language, as long as it has HTTP server capabilities.

I have chosen Python as language, since it allows us to create an HTTP server containing the business logic in one file.

A snippet of the webservice is shown below. The full script can be found here.

from BaseHTTPServer import BaseHTTPRequestHandler, HTTPServer

import json

class Controller(BaseHTTPRequestHandler):

def do_POST(self):

# Serve the sync() function as a JSON webhook.

observed = json.loads(self.rfile.read(int(self.headers.getheader("content-length"))))

desired = self.sync(observed["parent"], observed["children"])

self.send_response(200)

self.send_header("Content-type", "application/json")

self.end_headers()

self.wfile.write(json.dumps(desired))

def sync(self, parent, children):

# get parent specs

spec = parent.get("spec", {})

lambda_code = spec.get("code", "")

replicas = spec.get("replicas", 1)

host = spec.get("host", "localhost")

# Compute status based on observed state.

observed_status = {

"configmaps": len(children["ConfigMap.v1"]),

"services": len(children["Service.v1"]),

"ingress": len(children["Ingress.networking.k8s.io/v1beta1"]),

"pods": len(children["Pod.v1"])

}

# Generate the desired child object(s).

desired_children = [self.create_config_map(parent, lambda_code)]

desired_children.append(self.create_service(parent))

desired_children.append(self.create_ingress(parent, host))

for i in range(replicas):

desired_children.append(self.create_pod(parent, i))

return {"status": observed_status, "children": desired_children}

...

HTTPServer(("", 80), Controller).serve_forever()Alright, there is already a lot to digest here. Before showing the methods that create the actual child manifests, let us first understand the two method at the top:

def do_POST(self):The handler which is called when the POST request is invoked. It basically reads the request body as JSON and stores it in a variable called

observed. This contains the monitoredPythonLambdaresource, along with any children that were perhaps created in earlier runs. It can also be seen as the Current State. Lastly, it calls the next method to prepare the HTTP response.def sync(self, parent, children):This method is responsible for calculating the children based on the request data. This is called the Desired State. Metacontroller ensures to deploy the (changes of the) children to Kubernetes, when detecting differences. The method starts with reading in configuration from the spec part of the

PythonLambda, then calculates some status object about the current state, and finally calls all methods for generating the desired state of the child resources.

The snippet below shows two of the four methods generating child resources:

from BaseHTTPServer import BaseHTTPRequestHandler, HTTPServer

import json

class Controller(BaseHTTPRequestHandler):

...

def create_config_map(self, parent, lambda_code):

indented_code = map(lambda line: " " + line, lambda_code.split('\n'))

lambda_code = '\n'.join(indented_code)

return {

"apiVersion": "v1",

"kind": "ConfigMap",

"metadata": {

"name": parent["metadata"]["name"]

},

"data": {

"script.py": """

from BaseHTTPServer import BaseHTTPRequestHandler, HTTPServer

import urlparse

class Controller(BaseHTTPRequestHandler):

def do_GET(self):

query_params = urlparse.parse_qs(urlparse.urlparse(self.path).query)

output = ""

# Begin lambda

%s

# End lambda

if output == "":

output = "Lambda output was empty"

self.send_response(200)

self.end_headers()

self.wfile.write(output)

HTTPServer(("", 80), Controller).serve_forever()

""" % lambda_code

}

}

def create_pod(self, parent, i):

return {

"apiVersion": "v1",

"kind": "Pod",

"metadata": {

"name": "%s-%s" % (parent["metadata"]["name"], i),

"labels": {

"app": parent["metadata"]["name"]

}

},

"spec": {

"restartPolicy": "OnFailure",

"containers": [

{

"name": "hello",

"image": "python:2.7",

"command": ["python", "/scripts/script.py"],

"volumeMounts": [

{

"name": "script",

"mountPath": "/scripts"

}

]

}

],

"volumes": [

{

"name": "script",

"configMap": {

"name": parent["metadata"]["name"]

}

}

]

}

}

def create_service(self, parent):

return {

"apiVersion": "v1",

"kind": "Service",

...

def create_ingress(self, parent, host):

return {

"apiVersion": "networking.k8s.io/v1beta1",

"kind": "Ingress",

...

HTTPServer(("", 80), Controller).serve_forever()Let us take a look at those methods:

def create_config_map(self, parent, lambda_code):This method generates the Python script for starting an HTTP Server (seems familiar?), where the custom script of the developer (

lambda_code) is concatenated into theGETmethod handler.def create_pod(self, parent, i):This method generates the

Podwhich contains a container built from a Python image. TheConfigMapof above is mounted in the container in order for the container to run it. The parameteriis passed to it, because multiplePodscan be generated based on the number of replicas the developer configures. It is a number which will be added as suffix to thePodname.

Let’s run it!

Now we’ve got all pieces for running our PythonLambda with some custom code.

Here is an example which reads in the name query parameter, reverses that and writes that to the response body:

apiVersion: example.com/v1

kind: PythonLambda

metadata:

name: demo-python-lambda

namespace: python-lambda-operator

spec:

code: |

name = query_params.get("name", ["World"])[0]

reverse_name = name[::-1]

output = "Hello %s! Your name in reverse is %s" % (name, reverse_name)

replicas: 2

host: example.comAs explained in the “webhook service implementation” chapter, the three lines of code are combined with a Python HTTP Server template and put in a ConfigMap.

The replicas parameter ensures that two Pods are spun up running the code from the ConfigMap.

An Ingress resource is configured for the example.com host.

Now the following request can be done:

$ curl -XGET example.com?name=Martin

Hello Martin! Your name in reverse is nitraMConclusion

While it certainly looks like a lot of code for a blog post, it really is not a lot for what you get back for it. Metacontroller allows you to easily extend Kubernetes with powerful features, using simple APIs. If you think this was interesting, I encourage you to read about the Decorator Controller. This allows for changing the parent resource, in contrary to managing its children. Customize Hooks (currently only) allows for enhancing the webhook requests with related resources. This is extremely useful for when desired state should be calculated based on other resources than the parent and child resources. Once a watched resources gets deleted, the finalize hook allows you to clean up resources any way you like.

I’m very excited about this piece of technology, I hope I’ve conveyed some of this enthusiasm to you as well!